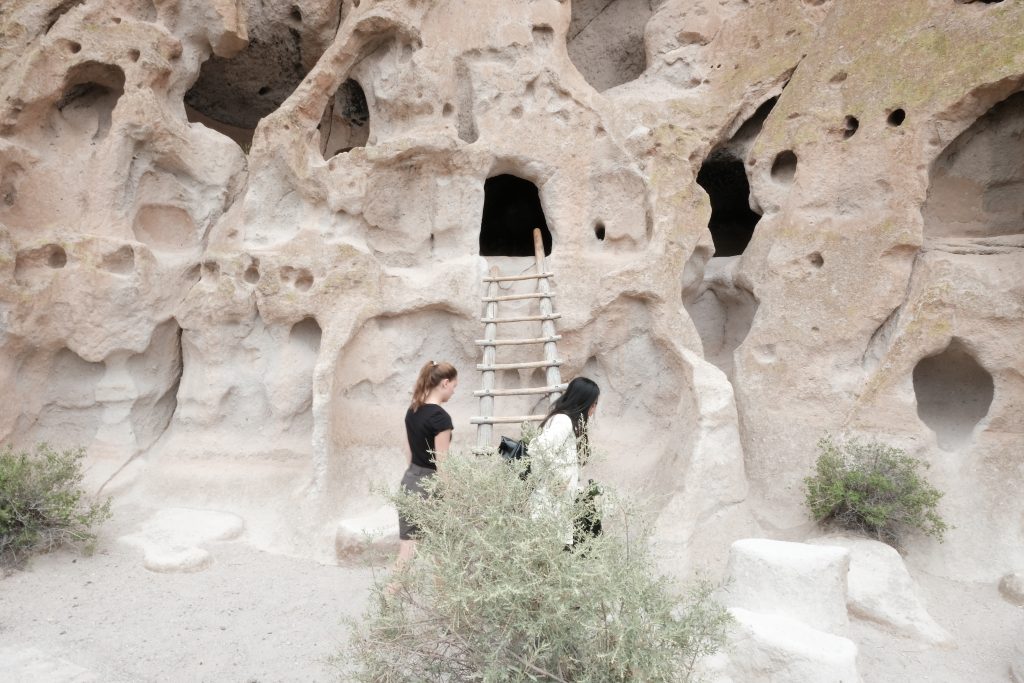

Continuing our exploration of innovative journeys within technology, we spotlight Gracie Meek and Jialei Tang from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Their recent project at the Bandelier National Monument is a remarkable intersection of cultural heritage and cutting-edge technology.

Meek and Tang used the BLK360 by Leica Geosystems, part of Hexagon, to create detailed digital models of the cave structures and cliff dwellings while working with the National Park Service to complete the project. The result is a first-of-its-kind digital model that preserves these ancient marvels and creates new possibilities for visitors to experience the park in the virtual world.

When people hear the name Harvard University, they’re probably not thinking about design as a focus. Still, the Graduate School of Design is a storied institution with amazing credentials and alums, including Frank Gehry and I.M. Pei. Can you tell us a little bit about your background and what drew you to the school?

Meek: I’m in my final year of the Master’s in Landscape Architecture program at Harvard. I came in with a background in architecture and wanted to expand the scale of my work. The degree itself seeks to innovate research and new design approaches that are aimed towards uniting the built environment with natural and ecological systems. My work in design focuses on bringing landscape-scale narratives like geological histories and climate patterns down to the human scale so we can experience them.

Tang: I graduated from the Master’s in Urban Planning program last May. Like Gracie, I come from architecture too, but I also studied philosophy concurrently in undergrad. And right there, I found my interest in the structure of knowledge resonating with my interest in architecture, which embedded the structure of things. Urban planning is another scale of structures.

Did you have a lot of STEM education in your primary education, then?

Meek: I was more of an artistically oriented student in high school, which drew me to architecture. I was fascinated by the ability to combine my artistic pursuits with the hard logistics of structure, and that brought me to Cornell University’s five-year Bachelor of Architecture program. In my final years at Cornell I became interested in working with public spaces and larger-scale design to integrate environmental factors, especially in the time of climate change.

Tang: I was also a humanities student in high school. I took something called “knowledge and inquiry”, and the philosophy of science was part of the curriculum. It showed me how science is a very self-critical discipline, which made me rethink STEM. Ultimately, I found myself in architecture because it was both art and science at the same time. Nothing is purely just arts or humanities, and nothing is purely just numbers and science.

That’s a real endorsement of the STEM approach! So, what drew you to Bandelier National Monument? That’s a long way from Boston.

Meek: I initially visited the site about five years ago on a family road trip. I was immediately taken by the site’s incredibly fascinating balance between the cliffside’s organic geologic formations and the Ancestral Puebloan people’s dwellings. The site was formed by a massive volcanic eruption about a million years ago that deposited a 300-foot-thick layer of ash. As this ash cooled and hardened, it left air pockets, which the Ancestral Puebloans further carved out and made into their homes. So, after that, I knew I wanted to document it in some dimension since it’s such a fragile site.

At the time, I just wanted to draw it. I didn’t know anything about laser scanning yet. But five years down the road, I met Lei [Tang], who’s also a huge rock nerd like me, and we learned about new laser scanning technologies like the BLK360 and some of the new techniques of digitally capturing environments to make digital replicas of the spaces.

Tang: When she showed me the site, I thought it was a hauntingly beautiful space. Because it’s hollowed out, and yet at the same time, it’s filled with stories and history and time collapsed into forms. It’s incredible how humans could do that without machines and build themselves a home in that climate.

Why is it important to you to gather scanning data on sites like this? Are you thinking more about the historical preservation aspect, or is it more about a new way to visually represent the place?

Tang: It’s in our nature to want to document things, whether before we design something like a building or look back at things we’ve already built. What’s alluring about this new technology is that we can record, document and understand something in a new dimension and digitise it to become sort of this immortal thing. The digital model can be a primary source for historians, artists, scientists or anyone interested in looking at it. There’s value in so many different disciplines.

How long did the scanning process take?

Tang: I think we were there for five days and four nights. Whenever there was an opportunity, we would scan. I want to say we got about six hours of actual scanning a day because we had to wait for when it wasn’t raining, we had to make sure the park was open and we had to work around tourists because we couldn’t just close the whole site while we gathered the data. Luckily, the BLK360 didn’t need wi-fi or a cell signal because there wasn’t any. And so, because of those limitations, we had to be very effective and fast and work 10 feet at a time to ensure we got it all.

Were you able to get scans of everything you wanted, or were there parts you had to leave out?

Meek: We got a lot more than we expected, actually! We thought we would just get the lower 20 or 30 feet of the cliffside, but we were shocked to see that the device recorded data all the way up, which is 300 feet tall. I mean, it’s unbelievable. The device was only three feet tall.

You got it all just from the ground?

Meek: Yes, we scanned point clouds every 10 to 15 feet to triangulate the different point cloud geometries to our positions. Through this, we got these complex curvilinear and concave forms that would have been hard to get otherwise. The point clouds at the top of the cliffside got much sparser, but we were amazed at how far it reached.

You already talked briefly about this, but what was the post-processing experience like? It seems like a monumental task, if you’ll pardon the pun.

Tang: It was tricky at first, but it eventually got a lot easier because we familiarised ourselves with the software. It was much more user-friendly than we anticipated, and the data was so beautiful and rich that it inspired us to do much more. Everything was so mesmerising that it expanded the timeline for producing the images. We also collected photographs we collated on-site, which paired well with the more molecular or haunting nature of the point cloud data in Reality Cloud Studio. That was something that we marvelled at, though, because it was a tool that allowed us to gather such precise information and inspire a lot of precise, beautiful and creative work at the same time.

So now that you have these models, is this something that could create virtual access to the space for people? Like a flythrough tour?

Meek: Absolutely, we used the Reality Cloud Studio platform a lot after we finished cleaning up and georeferencing the point clouds. We also filmed a lot of choreographed flythroughs, which we ended up using in a couple of presentations at Harvard last fall because it was straightforward to target specific areas that we wanted people to focus on and discuss.

We’re also working on an exhibit right now at Harvard, where we plan to use a touchscreen to display the Reality Cloud Studio platform so people can explore the point clouds on their own.

At some point, we want to project these point cloud flythroughs on a one-to-one scale so people can actually inhabit these spaces. Part of the project was bringing this amazing site back to Cambridge so people could experience it on their own, since it’s pretty remote and hard to get to.

What are the next steps for the project or for you in the future? Got big ideas?

Tang: One thing that really inspired me about this project was the idea of derivatives, which become a byproduct of something we’ve seen, touched or interacted with. It’s a reflection of the truth of that moment; it’s really inspiring. And to go back to what I was saying earlier, the exhibition we’re doing is going in a more artistic direction while also cataloguing and analysing the space scientifically. I think that’s the biggest takeaway of this project — it sets us in both directions and reminds us that you can always do something beautiful with something very quantitative and find some logic and structure and something very qualitative.

Meek: I’d also like to get in closer touch with the archaeologists at Bandelier. Part of the project’s point was to contribute these new documentation technologies to their existing ethnographic and archaeological sense of the area. Since we don’t have backgrounds in archaeology, I would love to find out what new insights they can derive from our data sets.

We’re highlighting stories from women in technology, so I wanted to ask: Do you see more representation of women in the space now?

Meek: I’d say so. We’re grateful to be in an environment where strong female representation is now the norm in our discipline. I am so grateful for the women who have come before us and paved the way for us to have the experiences that we do.

Tang: We never really saw ourselves as “women in STEM” because of the disciplines that we’re in. You know, we draw more than we use anything quantitative or scientific. But come to think of it, because both programs are considered STEM programs … yeah, there’s a lot of women. My department chair of Urban Planning is a woman. Two of the key instructors and professors who taught us how to code and use GIS are women, so it’s not something I found surprising; it’s just cool. But the more conversations I’ve heard about this topic, the more I realise what a privilege it is that it’s almost a norm for us today to see this many women in these positions and not be surprised by it.

I could ask questions about this project all day, but we’re out of time. So, what would you tell girls and women who are thinking about this kind of career path?

Meek: Take a lot of risks and be persistent. Just keep trying. You may fail or get rejected, but try again, fail, try again and keep trying new things. Keep pushing yourself instead of getting comfortable.

Tang: It’s also important to have that resiliency when taking those risks and not be afraid to fail but be very generous or forgiving of yourself at the same time. We don’t need to be hard on ourselves. It’s also advice to myself — keep trying, but remember it’s okay to fail, and you don’t have to feel bad about it.

Thank you both so much for sharing this with us. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Meek: I want to send our extended thanks to the Hexagon team for having so much faith and trust in us and for loaning us the equipment in the first place. Their support through the process was incomparable. We couldn’t have done it without them.

Tang: I can’t wait to try it out for other projects in the future!