It’s one of the most elaborate, culturally rich cities in the world. Artwork abounds as churches and chapels, all exquisitely designed, decorate every street. Home to 60,000 people, the city is surrounded by some of the most celebrated architectural and artistic monuments of all time.

This describes 15th-century Florence, and you can experience it today without leaving the comfort of your own home.

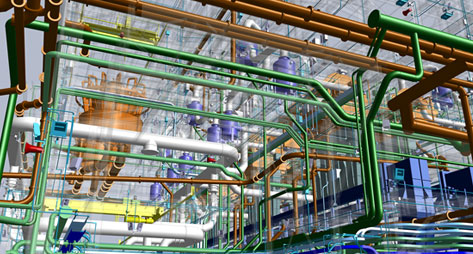

The Florence As It Was project uses Hexagon’s technology to bring the old city to life, creating digital twins of the city’s historical landmarks. These realistic 3D models result in an immersive, breathtaking new way to explore medieval and early modern history as if you’re living it in real time.

Embracing digital reality technology in education

David Pfaff and George Bent, colleagues at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, lead this project with infectious passion. In the words of Bent, an art historian of the Italian Renaissance, the project’s mission is “the gradual reconstruction of this major cultural center, one structure at a time, city block by city block.” Bent’s knowledge of Florence’s history and Pfaff’s expertise in computer science and imaging technologies allow them to create digital twins from complex structures and artwork, then annotate them with key bits of information to add context for each capture. Those annotations include building descriptions, translations, literary passages, musical performances and even tax records.

All this work allows their students – and the public at large – to explore Florence’s historical landmarks in detail, inside and out, as they appeared in the time of Leonardo da Vinci, free of charge. In these digital twins, virtual visitors can see photogrammetric recreations of paintings hanging where they were originally mounted hundreds of years ago. They can enter and navigate through spaces covered from floor to ceiling with elaborate frescoes. They can access annotations embedded directly into each digital twin, helping them discover art history in context. It’s a truly novel and personalised approach to education – one that Pfaff and Bent are pioneering in many ways.

“When I started teaching 30 years ago, my biggest complaint was I had to teach a sculpture or a painting that lived in a building, but my students couldn’t see the building,” Bent says. “That meant they couldn’t understand the context for what they were looking at. But I can now go into that space with my students so they can understand why those objects look the way they do.”

He describes using digital twins to walk with his students down the middle of churches. “I can say, ‘On your right, there’s a big chapel painted in 1492. Let’s go inside and examine how the images you see side-by-side there relate to one another and to ones on the adjacent or opposite wall.’” The spatial flexibility allows students to make new connections about an environment without being there.

Bent also points out that digital twins allow students to go where they usually are not allowed. “Today, in my classroom in Virginia, I took my students into the Florentine sacristy of San Lorenzo, which is where priests get dressed before Mass and is still in use today – and is therefore off-limits to the public. I was able to show my students two important altars and paintings there they never would’ve seen without this technology.” He also references the Santa Maria Novella digital twin, which allows students to explore the church’s rafters and attic between the vaults to see how the timber trusses hold everything together. “Nobody goes up there,” says Bent. “Art historians don’t even go up there. But now everyone can.”

He says this kind of usage is answering his biggest complaints from 30 years ago. “It’s totally changing the game in education.”

Explore the Santa Maria Novella with Dr. Bent’s digital twin flythrough video below.

Experience medieval Florence in a new way

Bardi di Vernio Chapel

The Bardi di Vernio Chapel was one of sixteen burial places for important Florentine families in the 14th century. Explore lifelike digital twins of the burial programme, tomb paintings and fresco cycles.

Verrocchio’s Bust of “Ginevra”

Orsanmichele

A gorgeous church dating back to 895 and completed in 1404, the Orsanmichele digital twin assembles more than one billion points to form an architectural model with a number of photogrammetric models of paintings inserted that were installed in the 14th century but removed in 1409. The reconstruction, perfected by Pfaff, includes a 3D colour model of the Sts. Cosmas and Damian painting, which currently resides in the North Carolina Museum of Art. “We were able to reintroduce that painting back into its original context in the 3D model,” Bent says.

Basilica di Santa Croce

Explore the interior of the Franciscan church of Santa Croce, which includes artwork by Giotto di Bondone in the (temporarily closed) Bardi Chapel through the realistic digital twin on Potree Viewer.

The future of digital immersive education

Dr. Bent fully believes in the potential of digital technology in art history because artists have always been among the most advanced adopters of technology. “Going all the way back to bronze, ceramics, the printing press – wherever there was new technology, artists were in on it,” he says. “That’s still true today.”

At the same time, he says each generation has their own expectations for how content gets delivered – whether that’s entertainment, social media, communication or education. “Students are going to be more advanced than the people teaching them, so their expectations will be higher. But I think the best way to teach students is to meet them on their own terms.”

Bent envisions a future classroom where every student can put on a mixed-reality headset and experience standing in a space along with their instructor and classmates. “That will give the teacher the luxury of walking through a space with a group and pointing things out to everyone,” he says. “That technology is prohibitively expensive right now, but in a few years’ time, universities will be able to afford them. That’s the near future for education.”

Preserving and protecting cultural heritage

The next steps for the Florence As It Was project include expanding, annotating and adding music to his vast database of 2,000 images rendering historical Florence. But the main goal remains the same as when Pfaff and Bent started six years ago: rebuilding and reviving the structures in Florence so they appear how they did in the 1500s. “Buildings always change,” Bent says. “When Notre Dame burned in 2019, restorers had to figure out which past version of Notre Dame to rebuild. They had to ask themselves, ‘Do we rebuild the original 12th-century version? The restoration in the 16th century? The total overhaul in the nineteenth? Which Notre Dame do we reconstruct?’” Bent says buildings have active lives, and it’s important to record them as they have changed over time.

Yet Bent is conscious about the ethical dilemmas implicit in his work. “Sometimes it feels like I’m taking someone else’s cultural heritage and sharing it online for the world. That’s a genuine concern in an AI world.” Bent says two things help him sleep at night, though. “The first is that we’re either asked by the proprietors of these buildings to come scan their buildings or, when we arrive, they wind up providing us with even more access than we originally requested – they actually invite us to come and explore their spaces with them. Clearly, they see the value in it and want it to be done.” As part of their long-standing policy, Bent and Pfaff give copies of the digital twins to the proprietors of each building for free.

“But secondly, we recognise that part of this work is preserving the past so in case anything happens, we always have a record of each structure. If the complex at Santa Maria Novella burned tomorrow like Notre Dame did, we now know exactly what it looked like and how to rebuild it to scale.” Digital twins have important uses didactically and archivally.

Bent and Pfaff’s project shows historians what’s possible with digital reality technology. With a glint in his eye, Bent says, “Now you can do things you could never do before.”

Learn more about the project at its website, Leica Geosystems’ case study or by watching the project’s documentary below.